By Jeremy Kennett.

This article first appeared in the Summer 2019 edition of our Primary Pulse magazine. Subscribe here.

Meet Hani. Hani is raising four of her five children alone in Melbourne with no support. Her son is being brought up in Somalia by his grandmother.

Hani arrived in Australia at eight years old and has experienced trauma throughout her life, including her sister dying in a house fire when she was 14. Hani feels guilty about her son being raised in Somalia and has struggled with mental health issues since the birth of her youngest child.

Now meet Katie. Katie is seven months pregnant and has an 18-month-old son. She is living in a caravan park with her partner Mike. Katie doesn’t feel safe in the caravan park and doesn’t want to bring her new baby home there. But with money tight and a poor rental history, they don’t have another option. She smokes and uses cannabis to relieve her stress, then worries about the impact on her baby. She feels judged by other parents and has withdrawn from her local playgroup.

Finally meet Anita. Anita’s 14-month-old son has poor eyesight and mobility issues. She too is now seven months pregnant and is worried about the baby’s weight gain. Anita is also suffering severe morning sickness that is affecting her mental health, and she has stopped taking her son to physiotherapy. Both she and her partner come from fractured homes and receive little support from their families. She is trying to engage with health services for herself and her children but some days she struggles to get out of bed.

Child and family health is a growing focus for our organisation, particularly in the growth corridors in the north and west of our region. We are working with service providers, community members and interested groups to identify the key health issues and vulnerable groups that we can help most through commissioning new and enhanced health services.

But what people like Hani, Katie and Anita remind us is that our work isn’t about targeting health issues or cohorts – groups of people who share particular social, cultural or economic characteristics. It’s about helping real people, people with individual needs, wants and worries.

Except Hani, Katie and Anita aren’t real people. All three are ‘personas’, created by combining the experiences, health issues and concerns of many real people.

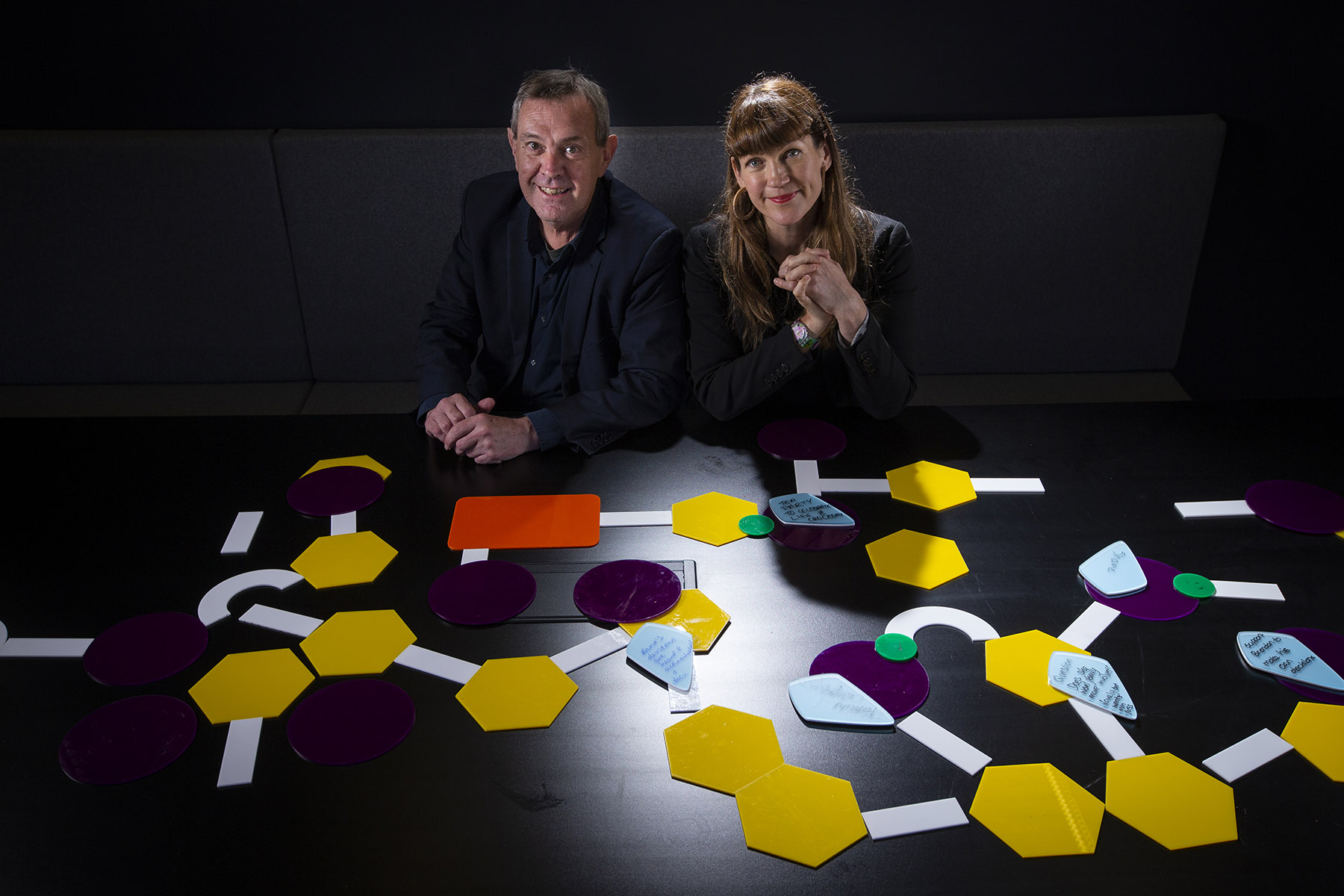

created as part of the Tactile Tools program.

Photo: Wayne Taylor.

They were created as part of a project to better understand local health needs by Better Health Plan for the West (BHP4W), specifically around families with low birth-weight babies. BHP4W is a regional partnership of diverse stakeholders, including North Western Melbourne Primary Health Network (NWMPHN), working to improve the health and wellbeing of people living in Melbourne’s western region.

Dr Leah Heiss and Dr Marius Foley from RMIT University’s School of Design led the creation of the personas as part of a broader project called Tactile Tools, compiling and compositing large quantities of de-identified health information and shaping it into representative individuals.

Dr Foley said their intention is to literally personify the particular health situation being examined.

“We think of them as semi fictitious,” he said. “They’re based on the experiences of people working in that space, compositions of different people with different circumstances.

“The photograph brings you to the person, and the text is designed to give a sense of who that person is, in terms of their age, maybe background, some significant things that they might have done. And something we’ve noticed is that the more realistic we can get those, the better they work.

“The persona asks the table to constantly come back to that person. . . To think ‘what does that person need in this situation? And what do they bring to it?’ And what are the critical incidents in their life that might be obstacles to them achieving that?”

The personas provide the starting point for looking at a health issue in a person-centred way, then the work of breaking down the problems and finding potential pathways to better care is done using the Tactile Tools.

Tactile Tools aren’t just theoretical – they are thin acrylic tiles in various shapes, sizes and colours, each representing a different part of a person’s experience.

“Goals are orange rectangles, roadblocks are yellow hexagons, work-arounds are purple circles and roads are white rectangular strips,” Dr Heiss said.

Dr Heiss developed the tools while working with a cancer hospital to help staff embed the organisation’s values into daily routines. The tools help health practitioners solve problems, design solutions and make decisions while keeping their organisation’s values “in mind, heart and hand”, Dr Heiss explains.

Dr Heiss has tested the Tactile Tools in cancer care, engineering and aged care and seen how they help diverse groups collaboratively design solutions.

“Within each of these situations the Tactile Tools helped participants to have difficult conversations, to be a designer at the table and use the power of prototyping to address complex design problems.

“They help us to address complex design problems such as ‘how can we deliver better cancer care?” or “how can we improve end-of-life experience?’”

Through several workshops the Tactile Tools process has helped the BHP4W partnership get a much clearer idea of the issues around low birth-weight, both systemic and individual, that need to be tackled in the region.

“What we were looking at was, what are the services that are wrapped around that family? And the person who’s organising it, how do they access those services? And where are the gaps that they might be falling through,” Dr Foley said.

“One of the great comments that came out of that workshop was, I think, from one of the doctors who said, ‘Look, we’re great at referring people, we’re not so good helping people transition from one set of services to another’.”

Participants were then able to use the tools to map out the issue, including obstacles and possible workarounds, while consistently working with the personas to ensure their pathways and potential solutions were grounded in individual experiences.

NWMPHN CEO Adjunct Associate Professor Christopher Carter said that while personas like Hani, Katie and Anita are not real people, they can teach us real lessons.

“Using innovative tools like the Tactile Tools and personas help ensure that the reforms and changes we make, and the programs we fund, always have the needs of individual people in mind,” A/Prof Carter said. “That is after all why we exist – to create better care for all of the more than 1.7 million individuals living in our region.”