By the Primary Health Care Improvement Team, North Western Melbourne Primary Health Network.

Background

It can be challenging to continue providing routine care during the pandemic; however, it is vitally important that usual screening practices continue. Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre has reported an approximate 20 per cent reduction in both referrals and patients attending routine treatments and appointments during the pandemic. This is a significant cohort of patients who are not accessing timely treatment.

Bowel cancer is the second most commonly diagnosed cancer in Australia (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer) and the second most common cause of cancer mortality. Australia has one of the highest rates of bowel cancer in the world.

The prevalence of environmental risk factors likely contributes to high rates of bowel cancer in Australia. These include physical inactivity and obesity, smoking, heavy alcohol consumption, and a diet high in red/processed meats and low in fibre.

Only around 30 per cent of people who develop bowel cancer have either a hereditary contribution, family history or a combination of both. The other 70 per cent have no family history of the disease and no hereditary contribution. If detected early, the chance of successful treatment and long-term survival improves significantly. Up to 90 per cent of bowel cancers can be successfully treated if detected early. Source

There are two types of bowel cancer screening available in Australia. The National Bowel Cancer Screening Program is a population-based screening program utilising faecal occult blood testing. Higher risk groups are screened with a combination of faecal occult blood testing and colonoscopy. GPs and general practice teams need to manage and refer patients with positive screening results and arrange screening colonoscopies for those at higher risk.

Expert commentary: Professor Jon Emery

Professor Jon Emery is the Herman Professor of Primary Care Cancer Research at the University of Melbourne, and the Victorian Comprehensive Cancer Centre Primary Care Research and Education Lead. He is also Director of the Cancer Australia Primary Care Collaborative Cancer Clinical Trials Group (PC4), and a Visiting Research Fellow at the Department of Public Health and Primary Care, University of Cambridge.

Professor Emery kindly offered to answer some frequently asked questions about bowel cancer screening for general practice.

The National Bowel Cancer Screening Program (NBCSP) sends a free faecal occult blood testing (FOBT) kit every two years to Australians aged between 50 and 74 years. However, for some higher-risk groups FOBT screening should be done annually and started at a younger age. Are there any avenues for access to funded FOBT kits for these people?

For those at moderately increased risk of bowel cancer, national guidelines recommend commencing biennial FOBT screening from 40-49 and then switching to five-yearly colonoscopy from 50-74.

GPs can request an FOBT kit through the MBS for this purpose, just as they ordered kits for screening when the full national biennial program had not been fully implemented.

You can order an FOBT through a normal pathology request and MBS will still pay for it. This was there when GPs were meant to be ordering two-yearly kits while the NBCSP was not fully implemented as a biennial program. I know there is this issue about MBS not officially supporting screening (but think of all the PSA tests done on the MBS!). There is still an item number for an FOBT (66764) and it does not state any limits on indication.

Do you have any tips for improving participation rates for my patients in the NBCSP?

There are several evidence-based ways general practices can improve participation rates. We know that any form of GP endorsement of the program is important – so even posters, leaflets or information on the TV monitors in waiting rooms can help. Opportunistic discussion in the consultation, prompted by reminder systems in the GP electronic record are effective.

More systematic ways include sending SMS reminders or endorsement messages near the person’s birthday when they are due to receive a kit. Cancer Council Australia created a practice toolkit with a range of additional resources to support practices who want to increase bowel cancer screening.

A patient returns a positive FOBT from the NBCSP. I recall them to explain the result and to arrange a referral for a colonoscopy. The patient tells me they would prefer to go publicly. How do I ensure that the referral is given the urgency it deserves?

The referral letter should state clearly that the person has had a positive test from the NBCSP. These referrals are prioritised by endoscopy units with a target of 30-days, although many public units still struggle to meet this target.

A patient returns a positive FOBT from the NBCSP. I recall them however they had a normal colonoscopy for surveillance just 9 months ago. They have no symptoms, and nothing to suggest haemorrhoids. How long is a normal colonoscopy good for? Should I still refer them to a gastroenterologist?

Assuming that there is nothing in the colonoscopy report to suggest incomplete examination (for example: poor bowel preparation or caecal intubation not achieved), the NBCSP recommends that there is no need to repeat the FOBT until four years after a normal colonoscopy.

I think most GPs deal with frequent inappropriate requests for screening colonoscopies for those with family histories of bowel cancer. Do you have a readily accessible version of the current guidelines you use? Do you have any top tips for discussing risk with patients?have a readily available

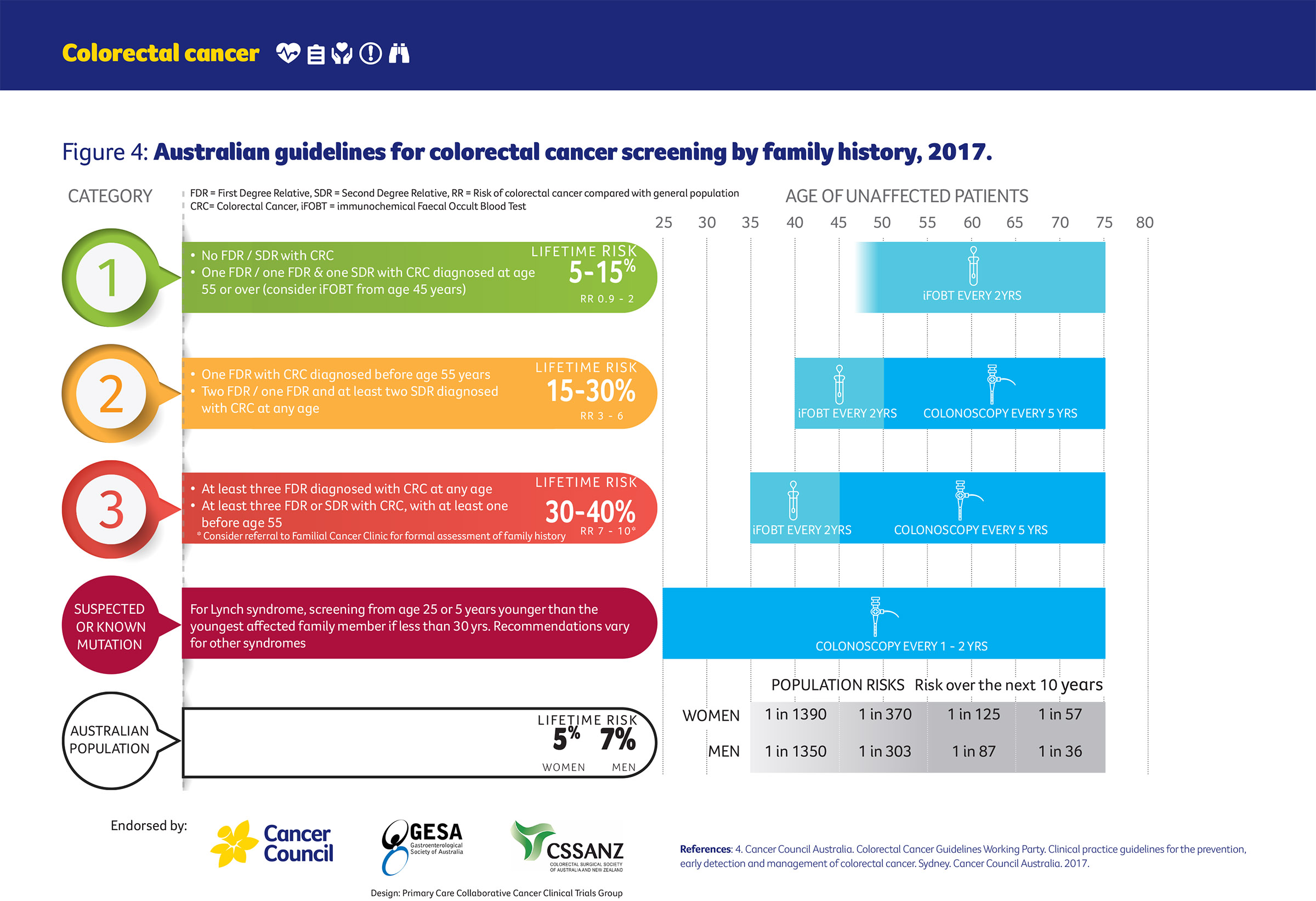

Our team has worked with Cancer Council Victoria to develop a series of tools about the Optimal Care Pathways (the I-PACED resources). These are available in information for Health Professionals section of the Colorectal Symptoms – Suspected Colorectal Cancer HealthPathway. The bowel cancer one includes a figure that summarises screening based on family history:

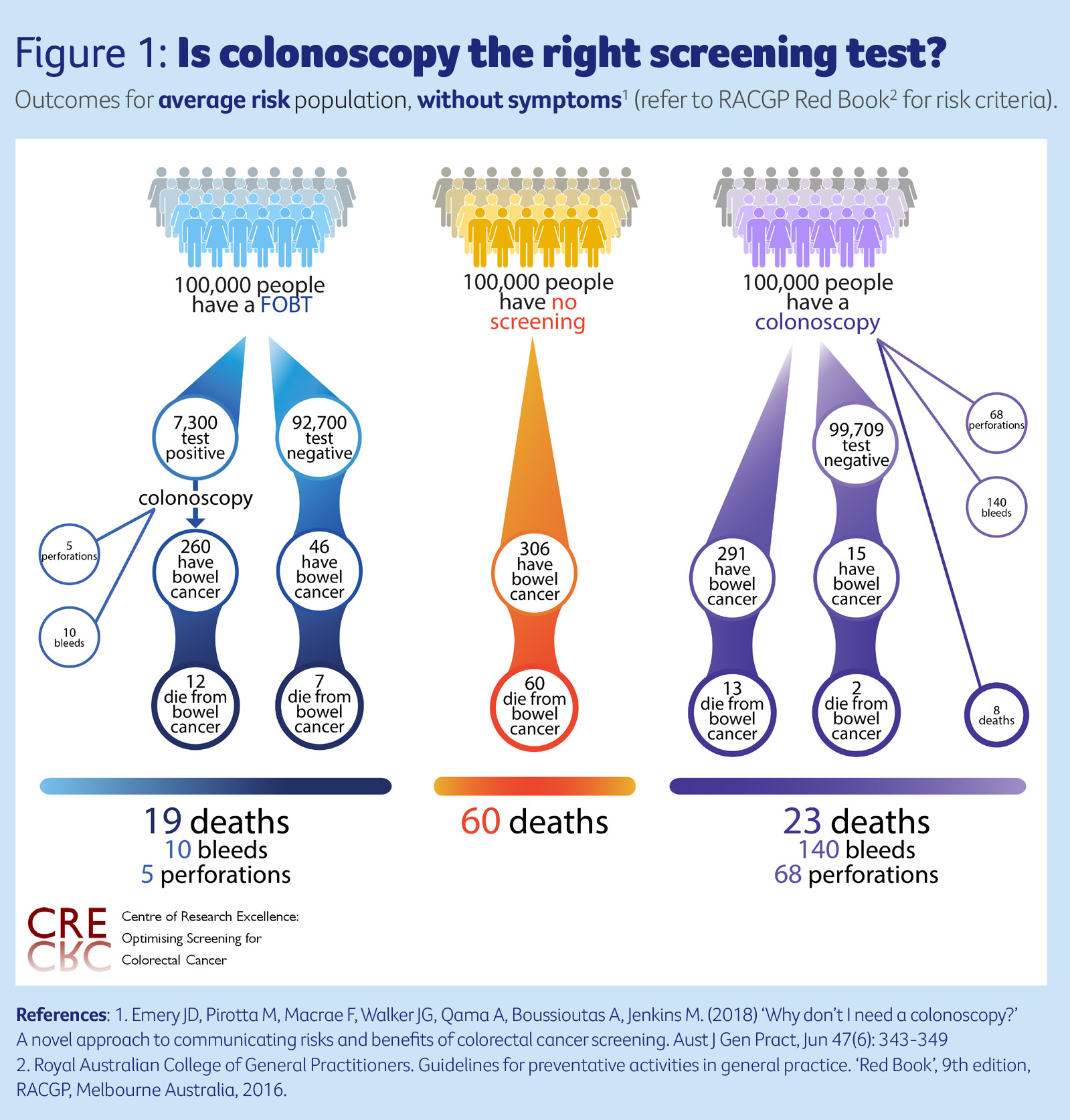

It also includes a decision aid showing why FOBT is the right test for people who are not at increased risk of bowel cancer:

I get very confused about how to stratify risk (as above) when a family member has had an adenomatous polyp rather than diagnosed bowel cancer. I generally proceed on the basis that without diagnosis these polyps may have become cancers. It seems unfair to me to penalise my patient’s access to screening because their relative was well screened. However, familial polyps (apart from syndromes) never seem to be included in risk stratification. How do I manage this?

The national guidelines group considered this when the guidelines were updated in 2017. Adenomatous polyps are relatively common once people reach the age of 50 and so a family history of a polyp is not a strong enough risk factor to place someone in the category of moderate risk of bowel cancer.

A patient once presented to me and told me their friend, who is a colorectal surgeon, recommended a baseline screening colonoscopy at the age of 50, and then stratified future screening based on this. How would you manage this request?

One of the difficulties is that there are large variations in international guidelines about which screening tests to use for bowel cancer. The national guidelines considered in depth the evidence about the relative benefits, harms and cost-effectiveness of different screening strategies for the population at average risk of bowel cancer. Biennial FOBT was by far the most cost-effective screening strategy.

The decision aid shown above is designed to support these types of request to show that FOBT is a much safer screening test and that colonoscopy should be reserved either for those at moderate risk of bowel cancer or people with significant symptoms.

Should I be recommending low-dose aspirin to all of my patients between 50-70 to prevent colorectal cancer, regardless of their risk stratification?

The national guidelines also reviewed the evidence about the effect of aspirin on bowel cancer risk. Low-dose aspirin (100mg daily for at least two-and-a-half years) reduces the incidence and mortality from colorectal cancer by 25 per cent and 33 per cent respectively. It is now recommended that all people aged 50-70 years, regardless of their bowel cancer risk, consider taking low dose aspirin – of course unless there are specific contraindications. People with cardiovascular risk factors have even more to gain from this approach. The decision aid below is also in the bowel cancer I-PACED resource.

More information

- Access the National Bowel Cancer Screening pathway on HealthPathways Melbourne. Need a login? Request access here.

- Australian Guidelines for Colorectal Cancer

- Colorectal cancer screening in Australia: An update (RACGP)