By Jeremy Kennett.

This article first appeared in the Autumn 2020 edition of our Primary Pulse magazine. Subscribe here.

Don’t get mad, get involved.

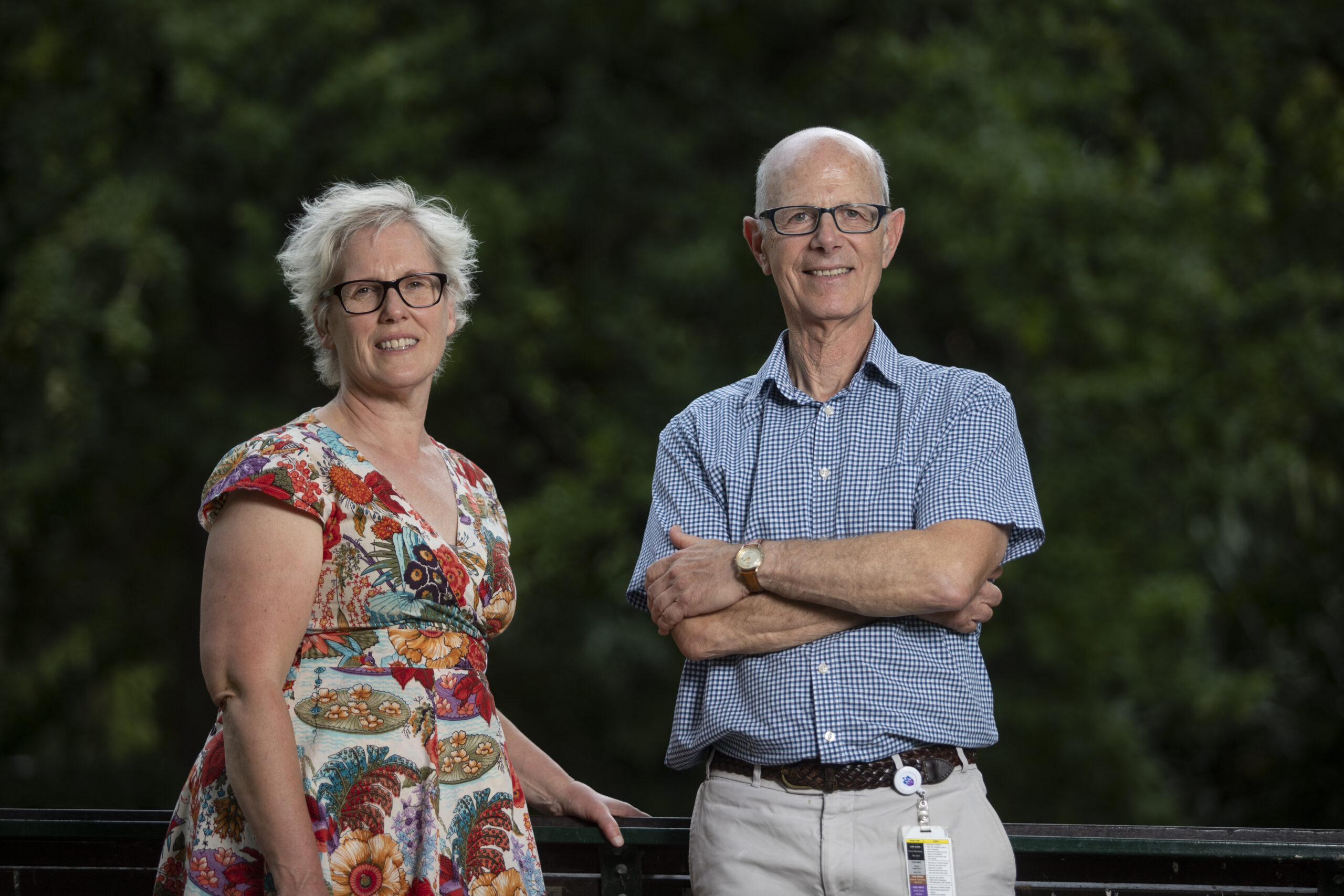

That was the attitude that led Dr David Isaac, a general practitioner in Richmond, to pioneer a program that has changed the face of GP engagement with hospitals across Melbourne – the General Practice Liaison Officer (GPLO) program at St Vincent’s Hospital.

Before becoming a GPLO two decades ago, Dr Isaac had become increasingly frustrated with the quality of communication between hospitals and GPs, especially when patients were being transferred between the two.

“When you are a GP and you’re sitting there, the patient’s come from hospital and you didn’t even know that they’d been admitted to hospital, let alone have a discharge summary and they come and tell you that all their medications have been changed but they can’t tell you what,” Dr Isaac said.

“They’ve had a whole lot of tests or even investigations and even procedures, and you’re just completely in the dark.”

The issue goes far beyond frustration for GPs, with the quality of communication having a direct impact on a patient’s risk of readmission and poor health outcomes.

“There was a study a few years ago which showed that patients who are discharged from hospital without a discharge summary [had] something like a 146% increase in readmission within a week . . . compared with those where a discharge summary was sent.

“When a GP has a patient in front of them where they’re completely in the dark about what’s been going on, they’re just going to put them in an ambulance and send them back to the ED.”

Repeated experiences like that led to Dr Isaac to establish a GP Liaison program at St Vincent’s Hospital in Melbourne. Since then most of Melbourne’s other major metropolitan hospitals, as well as several regional hospitals have also established similar programs.

Dr Isaac said the program’s value has been confirmed through Victorian health department assessments, especially in its contribution to clinical handover.

Dr Issac said the GP Liaison program is also supporting the Victorian health department’s move to standardise referral criteria used by GPs to refer patients to specialist hospital clinics. The GPLO program is just one way general practitioners and other health professionals are getting involved in areas of the health system beyond the traditional bounds of primary care – whether through interest or necessity. From the person-centred medical home model that places the GP as the conduit for the whole of a person’s health care, to health care workers in crisis situations like epidemics and disasters, the role of primary care is continuously expanding.

The push to get more GPs to cross over the primary versus tertiary divide isn’t only coming from GPs themselves. Adele Mollo, the Divisional Director of Women’s and Children’s Services at Western Health, is employing up to seven GPs to work in their antenatal clinic.

The new initiative coincides with a significant increase in births at Western Health since the opening of the Joan Kirner Women’s and Children’s Hospital last year.

“This year we’re predicting above 6,000 births,” Ms Mollo said. “So on average, we’re doing about 500 births per month.

“We’ve had to think very differently about the workforce model that we use to provide that antenatal care. And we’re excited to work with our primary health network and with GPs to look to integrate GPs into our antenatal care setting.”

Ms Mollo said GPs are such an important part of the care journey for women giving birth, so it makes sense to have them directly involved in hospital-based antenatal care.

“The fact that we can actually integrate general practitioners in our antenatal clinic means that women potentially will see this GP in the antenatal clinic and then will also be able to see the GP over a period of time as their family grows.

“It’s [also] beneficial for us as a health service to have an understanding of what happens in general practice.”

Ms Mollo sees the new collaboration as a way to increase capability for both hospital staff and general practitioners, meeting immediate need and aiding long term health workforce development.

“We have a real opportunity to build the confidence of the shared care component of maternity care. Potentially, this could become a rotational position that someone comes into the hospital and works with us for a 12 month period. And then once their skill set is built up in the capability level, we could then offer another GP an opportunity.”

Supporting GPs to communicate and work within the tertiary system isn’t just good for doctors and hospitals – it also has the potential to improve patient care, through better integration and consistency of services. It was a focus on improving health outcome for people that led Wendy Thomas to take up a role as a GPLO at St Vincent’s Hospital, despite not being a GP herself.

“I’ve seen it from the other side, the patient or carer side,” Ms Thomas said. “I’m going to try to make a difference because there’s a patient at the end and that could be me or my family or anybody.

“If the system issues in a hospital aren’t fixed or the system issues at the practices are fixed, then things aren’t going to link together so well.

“And once they’re linked together better then hopefully that will make a difference to the patient. The GP will know what’s going on with the patient, the patient might receive more targeted care.”

Building these links requires more than just the initiative of individual doctors and hospitals. It needs the commitment of funders at all levels to support greater flexibility and collaboration across the health and medical workforce.

A new National Medical Workforce Strategy, being developed as a partnership between state and federal governments, may go some way towards meeting these aims. The evolving strategy focuses on coordinating medical workforce planning, balancing generalist versus specialist skills and improving equity in health care access.

Consultations with health professionals and other stakeholders are underway, with the final strategy scheduled for release by the end of 2020. Beyond the strategy, Wendy Thomas says there are always opportunities for GPs to get more involved in improving their local health system.

“We’ve got a GP advisory group so GPs can get involved when there’s a place available, and other hospitals have the same, so they can get involved that way.” Ms Thomas said. “It’s not just about getting upset and frustrated about something – you can make a change.”